My Story

For additional photos and more of this story, follow along at the book's Instagram account @testimonythebook

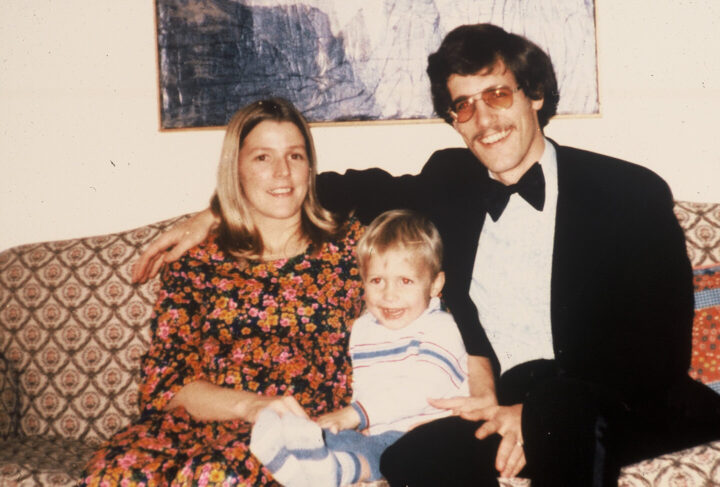

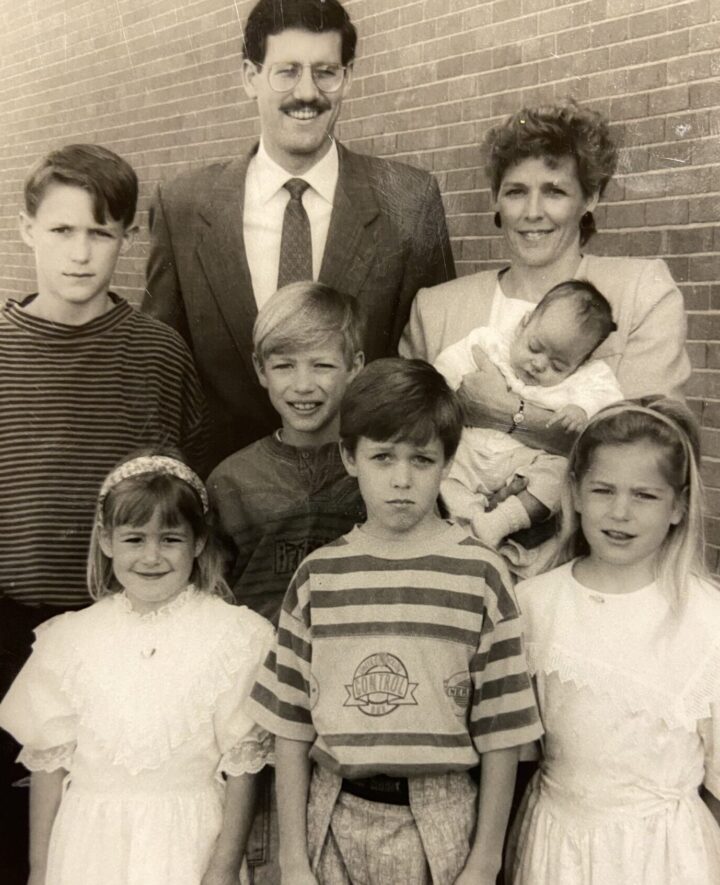

I was raised in the Maryland suburbs outside Washington, DC. We lived among the sprawling federal government workforce, full of middle-class families who commuted into the city each day. But we cocooned ourselves inside our church culture so tightly that we could have been anywhere: the plains of the Midwest or rural Appalachia. My dad and his friends were the pastors of this church, which he and his friends started in the mid-1970’s. He was the son of an All-American football star at the University of Maryland, and my mom was the daughter of a World War II veteran and a mother who was a meeting planner for the National Association of Counties.

Circa 1980

Circa 1980

I’m the child of a religious revival, a bona fide spiritual phenomenon that swept the nation in the 1970’s. My earliest years were saturated by this fixation with euphoric experience that had captured my parents’ generation. They were swept up in something called the Jesus Movement, which had begun at the end of the 1960s and spread throughout the country in the 1970s. My childhood was dominated by the story of this revival that they and their friends experienced in the years before I was born. And at the center of that revolution was this same thing I was taught to pursue: a personal, profound, emotional experience of God. But my Dad also schooled us in the book of Proverbs, which taught me to “search for [understanding] as for hidden treasure.”

A home church meeting

A home church meeting

The Jesus Movement was a special time. Those teens and twenty-somethings felt close to God and to one another. They came together and sang songs, broke bread, and held each other. They felt drawn into something big. It wasn’t just historic. It was eternal. It was life-changing. The Jesus Movement planted seeds of a radical Christian community. It promised to produce a Christian presence that had a prophetic edge in American life: captive to neither political party, speaking and acting boldly for the poor, the weak, the unborn, the neglected, and the downtrodden. This Christian presence would not be swayed by the appeals to fear used by demagogues over the ages.

In the 1980’s, my dad became active in protesting against abortion. My father’s path mirrored that of millions of White evangelicals in America. The shift wasn’t accidental; the Republican Party had identified abortion as a way to consolidate religious conservatives. They were able to merge religious conservatives like my father with cultural conservatives from the South who held on to their White supremacist views. Some scholars have argued that it wasn’t abortion that brought evangelicals into the Republican fold during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Instead, they say, it was racism and a reaction against the gains of the civil rights movement. But abortion was truly at the center of my parents’ worldview.

That’s Dad on the bullhorn

That’s Dad on the bullhorn

Throughout the 80’s, we were ensconced in the suburbs, going to a small school run by our church, which helped the leaders police nonconforming thought and behavior. Everything in our lives revolved around our church congregation, with the exception of our sports teams. Mom had her sixth child, and eventually a seventh. She was expected to stay home, and she did heroic work taking care of us all, even as she was marginalized. Our church culture had been created from scratch, out of nothing, just like the suburban landscape. There was no connection to the past, and little attempt to draw from the wisdom of tradition accumulated by previous generations. A vague emptiness washed over me as we drove endless loops through the suburbs. The more insular we became, the more incapable we were of discerning the complexities of the world outside our church bubble. We were ever more vulnerable to manipulation by those who told us that existential threats lurked around every corner. We were fearful, combative, and antagonistic members of the body politic, rather than stakeholders interested in and able to contribute to the greater good. We were well versed in private character, but completely unaware of the need for public character.

That’s me scowling on the left.

That’s me scowling on the left.

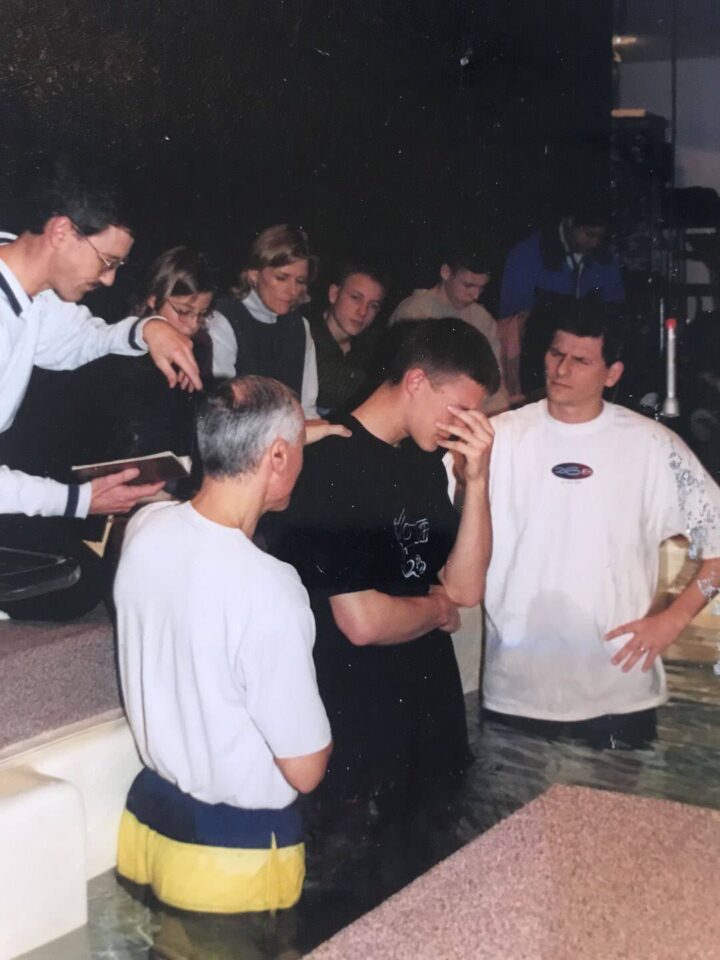

Around my 20th birthday, I became a religious fanatic. I was obsessed with living on an emotional high because I had been taught that this was the way to please God. I devoted myself to a strict behavioral code and to the hardcore Calvinist teachings that were newly in fashion in our church in the late 1990’s. I had a clarity about my purpose in life, and I took extreme measures to pursue it. But it was short-lived. I strained to live up to the exacting standards of moral perfectionism and endless self-examination, and I came to loathe myself. These were some of the unhappiest and loneliest years of my life. I was caught in a cycle of chasing emotional intensity, then failing to live up to an impossible standard of behavior in which I was taught to doubt my every motive and act. This led to depression and self-condemnation, and I strained to pull myself back toward a more righteous posture. I was suffocating under the weight of religion.

My baptism, 1997

My baptism, 1997

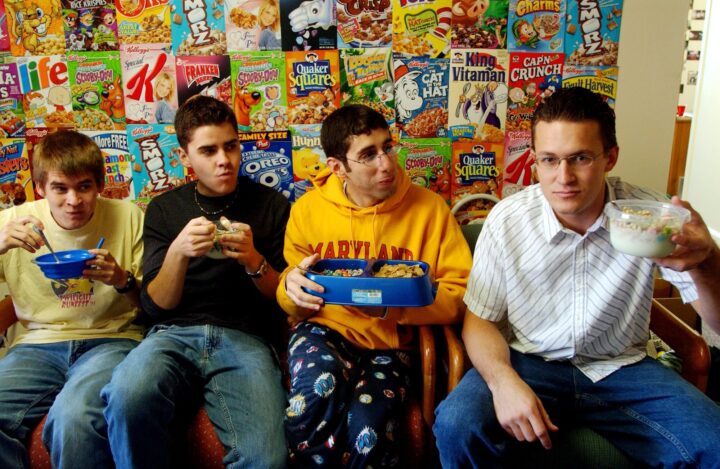

I was saved from fundamentalism, hubristic certainty and hopelessness by journalism. In 2001, I managed to get an unpaid internship at the Washington Times newspaper in D.C. I worked my way up to a desk clerk and then a reporter on the city desk. For the next few years I wrote about potholes, weather, zoning, local government, crime, and the like. I was apprenticed in a lengthy process of learning how to pursue facts. In Christianese — the often inscrutable dialect spoken inside many churches – I was being discipled in how to exercise discernment. But I also had a lot of fun. In 2003, I wrote an article about three college students who papered their dorm wall with cereal boxes. “Cereal has bonded these three young men and alienated their fourth suite mate, a lactose intolerant senior who they now call ‘the other guy,’ ” I wrote.

By 2007, I was covering the White House for the Times. During President Obama’s second White House press conference, I was called on to ask a question and pressed him on whether he’d wrestled with the ethics of embryonic stem cell research, and whether “scientific consensus is enough to tell us what we can and cannot do?” Obama said it was not, and that “there’s always an ethical and moral element.” My three years covering President Bush and President Obama took me around the world on Air Force One, and forced me to study up on global affairs and presidential politics. Around this same time, some of the leaders from my childhood church, such as Lou Engle and Che Ahn, were becoming more aggressively political and more clearly partisan actors in league with the Republican Party.

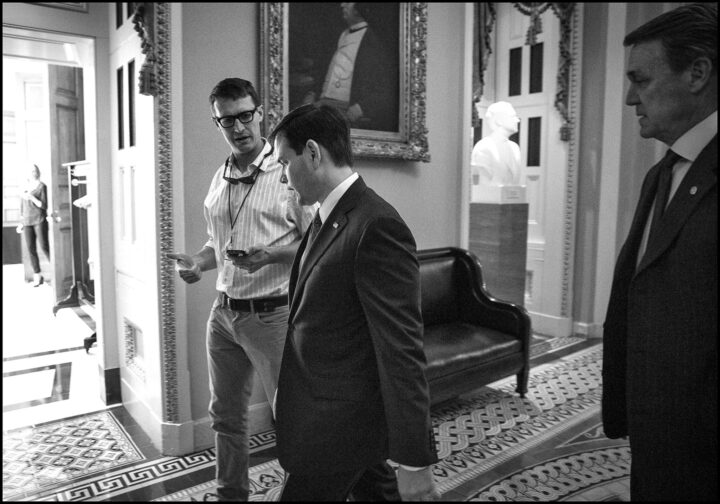

In 2009 I went to work for Tucker Carlson at The Daily Caller. I left a little over a year later, after I lost confidence in Tucker’s pledge to run a serious news organization. In 2011 I started at the Huffington Post, and started traveling to Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina ahead of the 2012 presidential election. I met Americans all over the country, asking them questions, listening closely to understand what they were thinking, and then trying to convey all this to our readership in my writing. Back in Washington, I felt more confident challenging politicians as I grew in my understanding and experience. In Maryland during this time, the church of my youth was disintegrating, as a culture of control, arrogance and insularity crumbled under the exposure of misdeeds and mishandled sexual abuse cases.In 2014, I was hired by Yahoo News.

With Sen. Marco Rubio in the U.S. Capitol, 2013.

With Sen. Marco Rubio in the U.S. Capitol, 2013.

My concerns about Trump’s fitness for the presidency never had anything to do with politics, partisanship, or ideology. “Trump is a dangerous threat to the foundations of our Democratic Republic that have for 240 years guaranteed all Americans freedoms of speech, thought, religion, commerce, and the press,” I wrote in an e‑mail to loved ones in the summer of 2016. My warnings about Trump’s scorn for the Constitution and the rule of law were dismissed as mere liberal bias. The 2016 result caused me to reflect deeply on how our politics had come to this point, as well as how in the world Christians had thrown in their lot with such a man. The deep fear that drove so many evangelicals to Trump was, to me, the opposite of how a confident faith could help Christians to stand for what was right. If so much of American Christianity had shown itself a fraud, how deep did the rot go? In 2020, I saw people I knew and loved departing reality and preparing to embrace authoritarianism. As I labored to combat a dangerous torrent of lies, my integrity was attacked by family members. It was a painful time of reckoning.

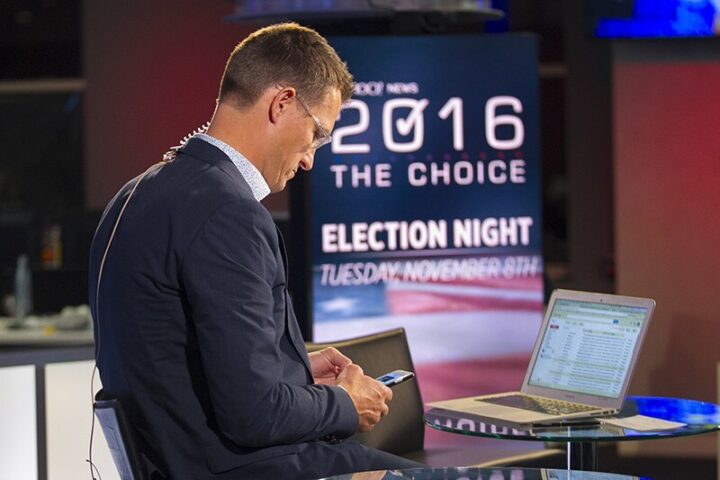

At Yahoo News HQ in New York City on Election Night.

At Yahoo News HQ in New York City on Election Night.

Since the 2020 election and the January 6 assault on the U.S. Capitol by Trump supporters, I’ve continued to work at Yahoo News. I’m still seeking to understand and explain the systemic causes of big problems, and to talk to those who are trying to come up with solutions. I’m working to make our politics more productive and our democracy more secure. I do this in my writing for Yahoo News, on my Border Stalkers Substack, and on my podcast, The Long Game. This is how I seek to live out my professional calling in a way that is Christian: generative, life-giving, and for the common good. Personally, I have been inspired by Mako Fujimura’s call to be “open to questions of meaning, reaching beyond mere survival, inspiring people to meaningful action, and leading toward wholeness and harmony.” There is a crisis of discernment in the American conservative church, caused by a failure of discipleship, and the church has lost its saltiness, its prophetic edge and independence in matters of public life and politics, as well as its spirit of mercy and sacrificial love. But there are sparks of light that signal a change.

Interviewing civil rights attorney Ben Crump, 2022.

Interviewing civil rights attorney Ben Crump, 2022.

For more photos and parts of the story, follow along at the book’s Instagram account @testimonythebook